Now that I have moved (at least partially!) into academic administration, my colleagues ask for advice on publishing strategy. A situation has occurred with one of my colleagues that has made me question my understanding of precedence of research results. I’d love some feedback to help me understand what went wrong here.

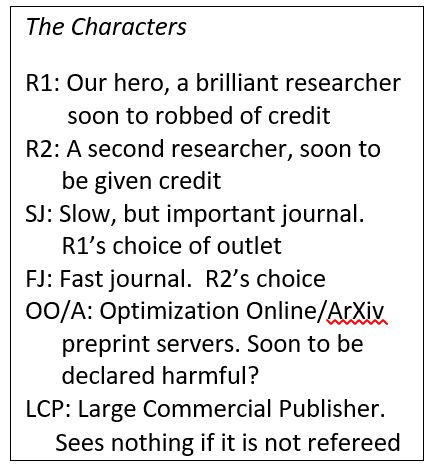

My colleague, call him R1, proved a couple theorems in a fast-moving subfield of optimization. He wrote up the results and on March 1 submitted the paper to The Slow but Prestigious Journal of Optimization, which I will call SJ (the characters get confusing, so the inset Cast of Characters may help). He also posted the paper on the well-known eprint servers Optimization Online and ArXiv (OO/A). The paper began its slow and arduous thorough refereeing at SJ.

On August 1, R1 received a perky email from researcher R2 with a paper attached saying “Thought you might be interested!”. The paper contains a subset of R1’s results with no reference to R1’s work. This is not a preprint however, but an “article in advance” for a paper published in Quick and Fast Journal of Optimization, QJ. QJ is a journal known for its fast turn-around time. The submission date of R2’s work to QJ is March 15 (i.e. two weeks after R1 posted on OO/A and submitted to SJ).

R1 lets R2 know of his paper, pointing to OO/A. R1 never hears anything more from R2.

R1 contacts the editors of QJ suggesting some effort be made to correct the literature with regard to the precedence of this work. QJ declines to change R2’s paper since it has already been published, and the large commercial publisher (LCP) does not allow changes to published articles (and, besides, R2 won’t agree to it).

OK, what about publishing a precedence acknowledgement in the form of a letter to the editor? I find this somewhat less than satisfying since the letter to the editor is separate from the paper and no one reads journals as “issues” anymore. But at least QJ would be attempting to correct this mess. And here is where I get both confused and outraged. The editor’s response is:

Also, during consultations with [LCP]’s office, it became clear that LCP does not approve of publishing a precedence acknowledgement towards a paper in public domain (preprint server). I hope you would agree that the fact that a paper is posted on a preprint server does not guarantee its content is valuable or even correct – such (partial) assurances can be obtained only during peer-review process.

Hold on, what? QJ and LCP are saying that they will ignore anything that is not in a peer-reviewed journal! R2 does not have to say anything about R1’s result since it has not been refereed. Further, unless R1 gets the paper published in SJ with the March 1 submission date, QJ will not publish a precedence acknowledgement. If the paper gets rejected by SJ and my colleague then publishes in Second Tier Journal on Optimization, clearly the submission date there will be after QJs date so R2 takes precedence. If the paper doesn’t get published, then R2 and QJ will simply act as if R1 and OO/A do not exist.

I find this situation outrageous. I thought the point of things like OO/A are to let people know of known results before journals like SJ finish their considered process of stamping their imprimatur on papers. If the results are wrong, then following authors at least have to point out the flaws sometime during the process.

Now I don’t know if R2 saw R1’s paper at OO/A. But if he did, the R1’s posting at OO/A at least warned him that he better get his paper submitted. Of course, R1’s paper might have helped R2 get over some roadblocks in R2’s proof or otherwise aid him in finishing (or even starting, though there are no overt signs of plagiarism) his paper. But it seems clear there was absolutely no advantage for R1 to post on OO/A, and clear disadvantages to doing so. R1 would have been much better served to keep his results hidden until acceptance at SJ or elsewhere.

This all seems wrong. R1 put out the result to the public first. How did R1 lose out on precedence here? What advice should I be giving colleagues about this? Here is what I seemed to have learned:

- If you don’t have any ideas for a paper, it is a good idea to monitor OO/A for results. If you find one, quickly write it up in your own words and submit it to QJ (but don’t post on OO/A). If you get lucky and the referees miss OO/A (or follow LCP’s rule and ignore anything not in the refereed literature), then you win!

- Conversely, if you have a result, for God’s sake, don’t tell anyone. Ideally, send it to QJ who can get things out fast. If you must, submit it to SJ but don’t post the preprint, present it at INFORMS, or talk about it in your sleep.

This all seems perverse. How should I think about this? Has anyone faced something similar? Does anyone see a satisfactory resolution to this situation? And, for those on editorial boards, does your journal have policies similar or different than that of LCP? Is this ever discussed within journal boards? Is all this a well-known risk?