Today’s New York Times Magazine has a very nice article entitled “Do Cellphones Cause Brain Cancer”. The emphasis on the article is on the statistical and medical issues faced when trying to find such a link. On the surface, it seems unlikely that cellphones have a role here. There has been no increase in brain cancer rates in the US over the time you would expect if you believe cellphones are a problem:

From 1990 to 2002 — the 12-year period during which cellphone users grew to 135 million from 4 million — the age-adjusted incidence rate for overall brain cancer remained nearly flat. If anything, it decreased slightly, from 7 cases for every 100,000 persons to 6.5 cases (the reasons for the decrease are unknown).

If it wasn’t for the emotion involved, a more reasonable direction to take would be to study why cellphones protect against brain cancer (not that I believe that either!).

This “slight decrease” is then contrasted in a later study:

In 2010, a larger study updated these results, examining trends between 1992 and 2006. Once again, there was no increase in overall incidence in brain cancer. But if you subdivided the population into groups, an unusual pattern emerged: in females ages 20 to 29 (but not in males) the age-adjusted risk of cancer in the front of the brain grew slightly, from 2.5 cases per 100,000 to 2.6.

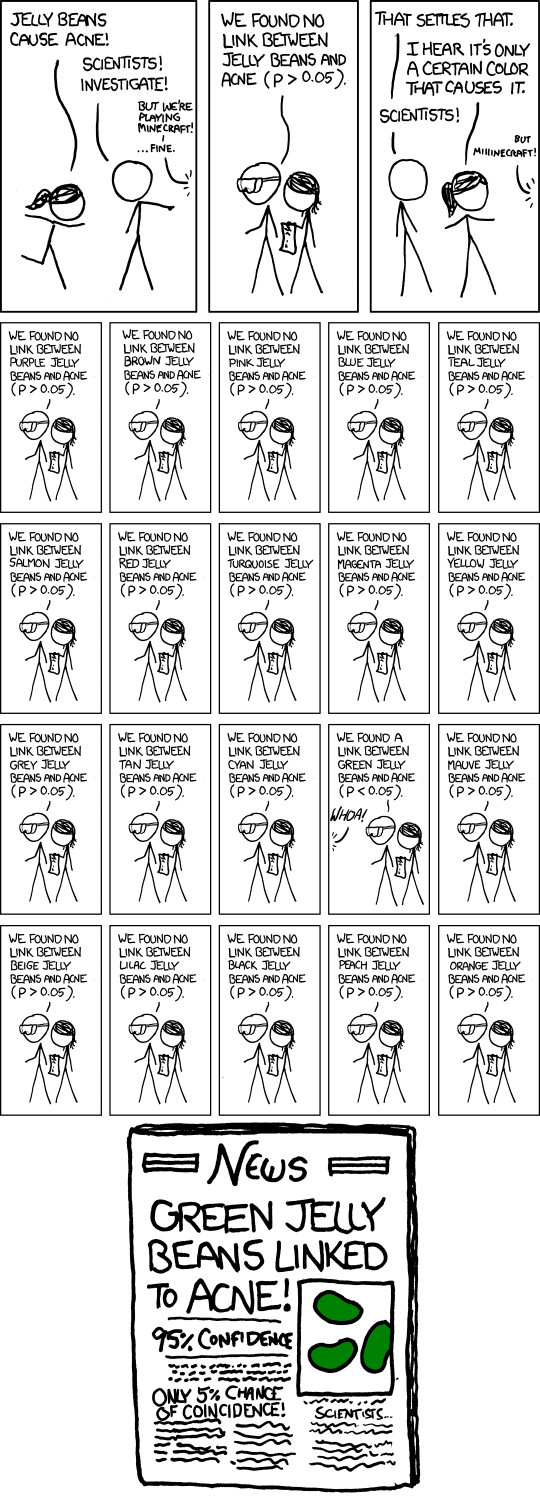

I am not sure why 7 down to 6.5 is “slight” but 2.5 to 2.6 is “unusual”. It does not take much experience in statistics to immediately dismiss this: the test divides people into males and females (2 cases), age in 10 year groupings (perhaps 8 cases), and area of brain (unclear, but perhaps 5 cases). That leads to 80 subgroups. It would be astonishing if some subgroup did not have some increase. If this is all too dry, might I suggest the incomparable xkcd.  If you test lots of things, you will come up with “significant” results.

If you test lots of things, you will come up with “significant” results.

Even if the 2.5 to 2.6 was “true”, consider its implications: among women in their 20s, about 4% of the occurrences of a rare cancer are associated with cell phone usage. This association would not be among men, or women 30 years or older or under 20. I am not sure who would change their actions based on this: probably not even those in the most at risk group!

And there are still a large number of caveats: the causation might well be associated with something other than cell phone usage. While statistical tests attempt to correct for other causes, no test can correct for everything.

There are other biases that can also make it difficult to believe in tiny effects. The article talks about recall bias (“I have brain cancer, I used my phone a lot: that must be issue!”):

some men and women with brain cancer recalled a disproportionately high use of cellphones, while others recalled disproportionately low exposure. Indeed, 10 men and women with brain tumors (but none of the “controls”) recalled 12 hours or more of use every day — a number that stretches credibility.

This issue is complicated by a confusion about what “causes” means. Here is a quick quiz: Two experiments A and B both show a significant increase in brain cancer due to a particular environmental factor. A had 1000 subjects, B had 10,000,000 subjects. Which do you find more compelling?

Assuming both tests were equally carefully done, test A is more alarming. With fewer subjects comes a need for a larger effect to be statistically significant. Test B, with a huge number of subjects, might find a very minor increase; Test A can only identify major increases. The headline for each would be “X causes cancer”, but the impact would be much different if Test A shows a 1 in 50 chance and test B shows a 1 in a million chance.

With no lower bound on the amount of increase that might be relevant, there is no hope for a definitive study: more and larger studies might identify an increasingly tiny risk, a risk that no one would change any decision about, except retrospectively (“I had a one in a zillion chance of getting cancer by walking to school on June 3 last year. I got cancer. I wish I didn’t walk to school.”). It certainly appears that the risks of cell phone usage are very low indeed, if they exist at all.

There is no doubt that environmental factors increase the incidence of cancer and other health problems. The key is to have research concentrate on those that are having a significant effect. I would be truly astonished if cell phones had a significant health impact. And I bet there are more promising things to study than the “linkage” between cell phones and cancer.

With articles like this I’m always reminded of Ioannides’s “Why most published research findings are false”.

Your last paragraph really hammers the important point home–for instance, studies which look at the “health effects” of driving while using a cell phone (health effects meaning crashing your car and hurting yourself and others of course) are easily much more useful than some of the headline grabbing cell-phone-cancer ideas.