Over the years, operations research, politics, and voting have intersected often for me. Going back almost 25 years now, I have done research on voting systems. I have blogged on elections, and written about predicting results and presenting results. I have written about political leaders who were trained in operations research, and even countries run on O.R. principles.

Over time, I have been both elated and disillusioned by politics at both the national and local scale. I use what I know about elections when I run committees, and get very frustrated by others running committees without an understanding of the basics of voting theory.

While I will not claim to be an expert on how theory and practice interact in politics and elections, I do have some insights. Many of these are well known to those in voting theory, but some are a little idiosyncratic. Perhaps we can have an election afterward on which is the most useful.

- When there are more than two possibilities, Plurality voting is just plain wrong. Plurality voting is what many of us (particularly here in the U.S.) think of as “normal” voting: everyone votes for their favorite and whichever alternative gets the most votes wins. We use this system a lot, and we should essentially never use it. The difficulties it causes with vote-splitting and manipulation are ridiculous. It is plurality voting that causes Republicans to support a left-wing candidate in the U.S. Presidential election (and vice versa for Democrats and a right-wing third party): if the third candidate takes votes away from the Democrat then the Republican has a better chance of winning.I feel strongly enough about this that I cannot be on a committee that uses Plurality voting: I will simply argue about the voting system until it changes (or until they start “forgetting” to tell me about meetings, which is kinda a win-win).

- I can live with practically any other voting system. There are quasi-religious arguments about voting systems with zealots claiming one is far superior than all the others. Nothing has convinced me: the cases where these voting systems differ are exactly the cases where it is unclear to me who should be the winner. So whether it is approval voting (like INFORMS uses), or some sort of point system (“Everyone gets six votes to divide among the candidates”), or multi-round systems (“Divide three votes, then we’ll drop the low vote getter and revote”) or whatever, most of it works for me.

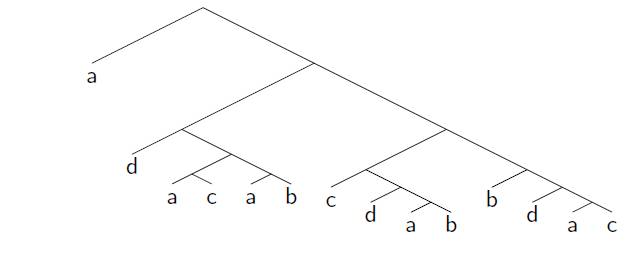

- The person setting the agenda can have a huge amount of power. While I may be happy with lots of systems, I am hyper-aware of attempts to manipulate the process. Once you give people the chance to think about things, then the agenda-setter (or voting-rule setter) can have an undue amount of power. Of course, if I am the agenda-setter, then knowing lots of voting rules can be quite helpful. Even without knowing committee preferences, it is handy to know that the following rule can help A win in an election with A, B, and C.

Let’s do B against C then the winner against A.

That is pretty obviously to A’s advantage (with voters voting their true preferences, A will win unless one of the others is a Condorcet winner — a candidate who could beat every other candidate in a two-person election). Less obvious is

Let’s do A against B, then A against C, then the winners against each other

This seems to favor A, but it does not. The only way A can win this election (with truthful voters) is for A to beat both B and C (hence be the Condorcet winner).

In fact, my research shows that you can arrange for A to win in a four-candidate election no matter what the preferences are provided A is not the Condorcet loser (loses to every other candidate in a pairwise election) and no other candidate is a Condorcet winner. Unfortunately, no committee is willing to sit still for the 12 votes required, beginning

We’ll go with A against B, then A against C, then take the winners against each other, and take the winner of that against D, then…

This leads to my favorite voting tree, as in the diagram.

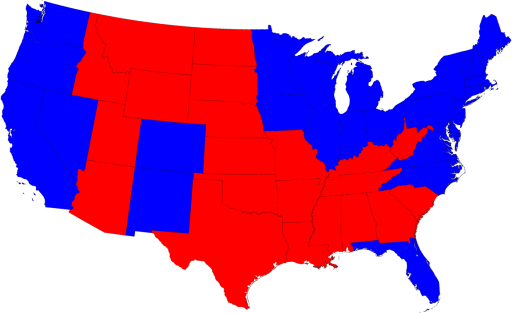

- When there is block voting, power is only weakly related to the size of the block. I have in mind systems where different “voters” have different numbers of votes. So, in a parliamentary system with party-line voting, if there are 40 representatives for party A, then party A gets 40 votes. It might seem that if the overall support is 40% for party A, 40% for party B, and 20% for party C, then it would only be fair to give parliamentary seats in that proportion. Unfortunately, if bills need 50% of the vote to pass, “proportional representation” gives undue power to party C. In fact, in this case C has as much power as A or B: two of the three parties are needed to pass any bill. Conversely, if the support is 51%, 48%, 1%, and a 50% rule is used to pass, then the first party has all the power.

This simple observation has helped me understand the various issues with the recent U.S. Senate vis-a-vis the filibuster rules (which essentially required 60% of the votes to move anything of substance forward): the Senate vacillated between having the Democrats having all the power (51 votes to pass a bill) and having Democrats and Republicans having the same power (60 votes to end a filibuster). With no solution representing reality (either 58% of the Senate seats for the Democrats or perhaps a lower number representing nation-wide party support), the system cannot equate power with support.

This is seen even more starkly in the election of a single individual like the U.S. President. George Bush in 2004 claimed a “mandate” after winning 51% of the popular vote. While 51% might not seem like a mandate, it is difficult how else to map 51% to a single person.

Understanding this power relationship makes U.S. Electoral College analysis endlessly fascinating, without adding much insight into whether the Electoral College is a good idea or not.

- The push towards and away from the median voter explains a lot about party politics. One fundamental model in economics is the Hotelling Model. Traditionally this model is explained in terms of ice cream vendors along a stretch of beach. If there is one vendor, he can set up anywhere on the beach: he has a monopoly, so no matter where the beach-goers are, they will go to the vendor. But suppose there are more than one vendor and beach-goers go to the closest vendor. If there are two vendors, the only stable place for them to be (assuming some continuity in the placement of beach-goers) is to have both at the median point, right next to each other! This seems counter-intuitive: why aren’t they, say, 1/3 and 2/3 along the beach (for the case of uniformly distributed beach-goers)? In that case, each vendor gets 1/2 of the customers, but the vendor at 1/3 would say “If I move to 1/2 then I’ll get 5/12 of the customers, which is more than my current 1/3”. Of course, the vendor at 2/3 also has an incentive to move to the middle. So they will happily set up next to each other, to the detriment of the beach-goers who must travel farther on average to satisfy their needs.

How is this related to politics? I believe it gives the fundamental pressures on parties in two-party systems. In the U.S., both the Democrats and Republicans are pressed towards the middle in their efforts to get to the median voter. But the most interesting aspects are the ways in which the political system does not meet the modeling assumptions of the Hotelling model. Here are a couple:

- The Hotelling Model assumes customers will purchase no matter what distance they need travel to the server. In a political model, voters sufficiently far away from all candidates may simply choose not to participate. While non-participation is often seen as abdicating a role, that need not be the case. Take the case of the “Tea Party Movement”. There are many interpretations of their role in politics, but one threat to the Republicans is a willingness to of the Tea Partiers to simply not participate. This has the effect, in a simplistic left-right spectrum model, to move the median voter to the left. If the Republicans want to move to the resulting median, they would have to hop over the Democrats, something that is simply infeasible (the effort to convince the left wing will take generations to believe the Republicans are really their party). So the threat of non-participation is a strong one, and can only be counteracted by the Republicans by having policies sufficiently appealing to the Tea Partiers to keep them participating. Of course, this rightward movement opens the opportunity for the Democrats to appeal to the crowd in the resulting gap between Democrats and Republicans, though the Democrats undoubtedly face non-participation threats at their own extremes.

- Another sign of the pressures towards and away from the median occur in the primary/general election form of U.S. politics. During the primaries, a candidate (either local or national) needs to appeal to voters in their party (in most cases). This leads to movement towards the median of a party, particularly if there are only two candidates. Once the candidate has been chosen by the party, though, the candidate is now facing median pressure from the general population. this should result into a movement towards the center, which certainly seems to be the case. Party activists try to stop this move towards the center by forcing pledges or other commitments on candidates, which keep them more towards the median of their own party, perhaps at the expense of general election success.

The Hotelling Model in politics is a wonderful model: it is wrong but useful. By understanding how the model doesn’t work, we can get insight into how politics does work.

It would be easy to be disillusioned about voting and politics based on theory (and practice, some days). No voting system is fair or nonmanipulable; pressures on candidates force them to espouse views that are not their own; consistency is obviously a foible of a weak mind.

Instead, my better understanding of voting and elections through operations research leaves me energized about voting. However imperfect it is, the system does not need to be mysterious. And a better understanding can lead to better systems.

This topic has been on my list of “to-do”s for a while. I am glad that the Second INFORMS Blog Challenge has gotten me to finally write it!