Or perhaps own two tons of Operations Research History (I am not sure how much 70 bankers boxes weigh)! And not just any history: this is the mathematics library of George B. Dantzig, available by “private treaty” (i.e.: there is a price; if you pay it, you get the whole library) from PBA Galleries. I suspect everyone who reads this blog knows who Dantzig was, but just in case: he is the Father of Operations Research. His fundamental work on the simplex algorithm for linear programming and other work should have won the Economics Nobel Prize. He had a very long (spanning the 1940s practically to the end of his life in 2005) , and very influential, career. You can read more about him in this article by Cottle, Johnson, and Wets.

Or perhaps own two tons of Operations Research History (I am not sure how much 70 bankers boxes weigh)! And not just any history: this is the mathematics library of George B. Dantzig, available by “private treaty” (i.e.: there is a price; if you pay it, you get the whole library) from PBA Galleries. I suspect everyone who reads this blog knows who Dantzig was, but just in case: he is the Father of Operations Research. His fundamental work on the simplex algorithm for linear programming and other work should have won the Economics Nobel Prize. He had a very long (spanning the 1940s practically to the end of his life in 2005) , and very influential, career. You can read more about him in this article by Cottle, Johnson, and Wets.

At the auction site, there are also some reminiscences from his daughter Jessica Dantzig Klass. She talks about some of the books in the library:

I found two copies of Beitraege zur Theorie der linearen Ungleichungen, Theodore S. Motzkin’s dissertation, translated “Contributions to the Theory of Linear Inequalities.” This work anticipated the development of linear programming by fourteen years and is probably the reason Motzkin is known as the “grandfather of linear programming”. A close family friend, Ted, as he was known, was a gentle, mild mannered man, with intense eyes, and a sweet smile, and he “lived” mathematics, even keeping small pieces of paper by his bed, so that when he had an idea at night he would be able to write it down. His dissertation is interesting from an historic perspective; bridging the gap between Fourier and my father’s work. Ted, a student at the University of Basel in Switzerland, was awarded his Ph.D. in 1933, but it was not published until 1936 in Jerusalem. One can trace the mathematical lineage of Motzkin’s advisor, Alexander Ostrowski, back to Gauss. And until his untimely death in 1970, Motzkin was my husband’s Ph.D. advisor at UCLA.

I don’t know how expensive the collection is (and I certainly don’t have room for 70 bankers boxes of material), but it would be great if an organization (INFORMS, are you listening) or a historically-minding researcher picked this up. I suspect in the future, there will be far fewer libraries from great researchers. I know that my own “library” is really nothing more than the hard drive on whatever computer I am using.

For finding my ancestry, the first part is easy: John Bartholdi was a student of Don Ratliff (starting me on a non-branching family tree), and Don was the student of

For finding my ancestry, the first part is easy: John Bartholdi was a student of Don Ratliff (starting me on a non-branching family tree), and Don was the student of

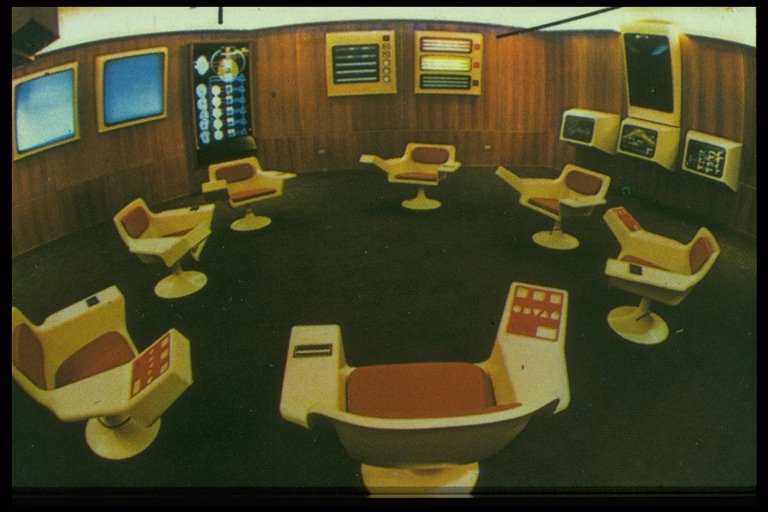

The system, named Cybersyn, had its greatest success in reaction to a country-wide strike. There is a

The system, named Cybersyn, had its greatest success in reaction to a country-wide strike. There is a