This blog has been around more than six years, making it ancient in the blogosphere. And, while not popular like the big-boy blogs (I run about 125,000 hits a year with about 1500 RSS subscribers according to FeedBurner), I think I have a reasonable-sized audience for the specialized topic I cover (operations research, of course!). People recognize me at conferences and I get the occasional email (or, more commonly, blog comment) that lets me know that I am appreciated. So I like blogging.

The past few months, however, have been a chore due to the amount of comment spam I get. Of course, I have software to get rid of most the spam automatically (Akismet is what I have installed), since otherwise it would be unbearable. Akismet stopped 5,373 spam comments in the last year. This sounds like a lot but that is way down from the heights a few years ago: Akismet stopped 6,711 spams in the month of March, 2009 alone. Unfortunately, it is letting a lot more spam come through for me to judge: in the past year 619 entries were put through to moderation that I determined were spam. This is a frustrating exercise since I like my readers: if they want to say something, I want them to say it! But comment after comment from places like “Sacremento Cabs” or “Callaway Reviews” saying vaguely on-topic things is a bit hard to take. Sometimes it seems that someone has taken the effort to read the blog post and comments:

“From the communication between the two of you I think I can say that I wish I had a teacher like Mr. X and I wish I had a student like Y.”

came in recently, where Mr. X and Y were previous (legit) commentators. But the URL of the commentator was to some warez site, so I deleted it all. Is this a human posting, or just some pattern matching?

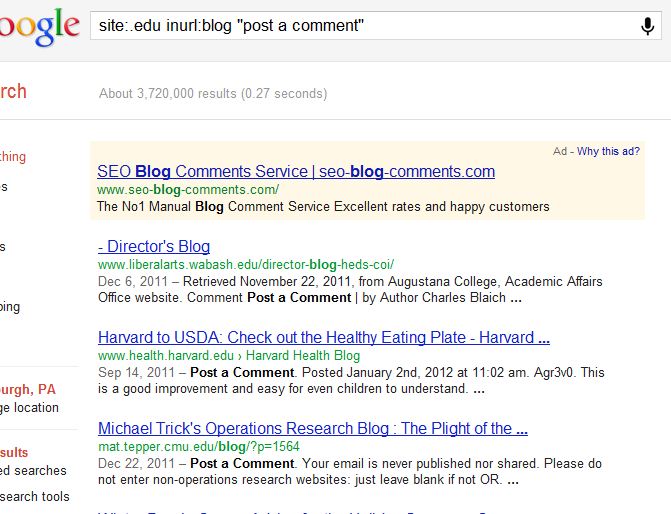

Why the sudden influx? Further checking the logs showed that a number of people (a couple hundred per month) are getting to this blog by searching something like ‘site:.edu inurl:blog “post a comment”‘. Sure enough if I do that search (logging out from google and hoping I get something like a generic search result, I get the following:

Wow! Of all the .edu blogs that include the phrase “Post a Comment”, I come in at number 3! Of course, despite my efforts, Google may still be personalizing the search towards me, but clearly I am showing up pretty high to attract the attention of hundreds of people. Through my diligence and efforts, I have made this blog attractive to the Google algorithms (I do seem to be number 1 for “operations research blog” and some other natural searches). This is a great Search Engine Optimization success!

Or not. Because clearly I am attracting lots of people who have no interest in what I have to say but are rather visiting to figure out how they can manipulate me and the blog for their own non-operations research purposes (I am perfectly happy to be manipulated for operations research purposes!). The sponsored link in the search gives it away: there are companies working hard to get comments, any comments, on blogs (presumably any blogs). How many of those 125,000 hits were really my audience (people in operations research or those who would like to know more about it)? Do I really have an operations research audience at all (beyond Brian, Matt, Laura, and a few others who I know personally)?

I’ll spend time thinking about ways to avoid this aggravation. I’ve already put in NOFOLLOW tags, so there is no SEO value to any URLs that get through. I already warn that if the URL submitted is not on operations research, then the comment will be deleted. I could get rid of URLs completely, but I do see legitimate comments as a way of leading people to interesting places. I could add more CAPCHAs and the like, though I am having trouble with some of those myself, particularly when surfing with a mobile device. Or I can put up with deleting useless comments with inappropriate URLs and just relax about the whole thing. But fundamentally: how can you do Search Engine Optimization to attract those you would like to attract without attracting the attention of the bottom-feeders?

On the off chance that one of the …. shall we say, enterprising souls, has made it through this post, perhaps you can explain in the comments why you add a comment when the topic is of no interest to you. Do you get a dime for every one that makes it through? Are you bored and find this a useful way to pass a quiet afternoon? Are you a program, mindlessly grabbing parts of the post and comments to make yourself look more human? Add a comment: I probably won’t let your URL through but at least we can understand each other a bit better.

For finding my ancestry, the first part is easy: John Bartholdi was a student of Don Ratliff (starting me on a non-branching family tree), and Don was the student of

For finding my ancestry, the first part is easy: John Bartholdi was a student of Don Ratliff (starting me on a non-branching family tree), and Don was the student of