If you are not at the INFORMS Practice Conference, you missed a plenary talk this morning that worth the price of admission alone. Chris Lofgren, President and CEO of Schneider National, gave a talk that was, at its heart, about being a successful OR professional, whether working as an analyst or working as a CEO.

I have known Chris since 1982 or so, when we started in the PhD program at Georgia Tech together. Chris could have been a successful academic (his work on scheduling flexible manufacturing systems still gets referenced) , but he chose a different path, and has been incredibly successful. He started at Semantech, then Motorola, but has spent most of his career at Schneider National, the largest truckload carrier in North America. Along the way he was the CIO, COO and since 2002 has been President and CEO (see the CIO magazine article on his path from CIO to CEO).

I have known Chris since 1982 or so, when we started in the PhD program at Georgia Tech together. Chris could have been a successful academic (his work on scheduling flexible manufacturing systems still gets referenced) , but he chose a different path, and has been incredibly successful. He started at Semantech, then Motorola, but has spent most of his career at Schneider National, the largest truckload carrier in North America. Along the way he was the CIO, COO and since 2002 has been President and CEO (see the CIO magazine article on his path from CIO to CEO).

Chris credits his success, in part, to the skills and training he received in OR. “Not a day goes by that I don’t use the my education and background”, he said. Before the talk, he told me a story of talking to executives of a large retailer and noticing that the problem they were faced with could be solved by linear programming, and the duals actually would give the information they needed. It is nice seeing a CEO still thinking that way! Most of the time, of course, the OR background comes through in the analytical, data-driven way he makes the tremendous number of decisions a CEO must make.

His talked revolved around six themes:

- Insight

- Importance

- Simplicity

- Robustness

- Breakthrough

- Three Secrets (that aren’t secrets at all)

The talk was peppered with quotes and thoughts from his experiences. For instance, on insight, he noted that it was less important that a variable had a value than understanding why a variable had that value. Once you have that understanding, you are able to give senior executives the walk-away piece of information they need.

One point that really hit home was during his discussion on breakthrough: the need to understand things in perhaps radically different ways. As Chris said: “It is what you don’t know that you don’t know where you find the breakthrough”. During this discussion, he drew a distinction between “Making things better” versus “Making better things”. In operations research, we spend an awful lot of time on making things better: we improve schedules, we reassign work forces, we design transportation systems. And this is important! But even more important is to use the insights we have to create breakthroughs on processes and products to result in better things. The example he gave was a project we had worked on together for Motorola. Together, we figured out a better way to schedule a particular machine making printed circuit boards and we cut the time needed to make these boards by 10% or so, which saved the company millions. But the next step is one we could see: we gained insight into how to redesign the board to result in enormous savings. The redesign went against all the common wisdom, since it involved much more expensive components, but the system-wide savings would dwarf those immediate costs.

The “three secrets” that aren’t secrets are:

- No one cares how smart you are (though Chris bonded with the audience by saying how smart us OR people are): people care about how you can help them … speak their language.

- If you dare to make better things, you will push against the status quo and need courage in your convictions

- There is no right way to do the wrong thing. Solve the right problem or don’t solve anything.

This summary can only give the bare bones of Chris’ talk. By backing up his thoughts with concrete examples from his experience (particularly his OR experience), he gave a talk that I found both insightful and inspiring!

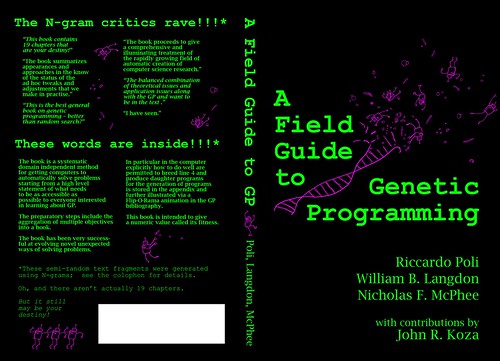

Ricardo Poli, William Langdon, and Nicolas McPhee have just published a book

Ricardo Poli, William Langdon, and Nicolas McPhee have just published a book  If you have taken an undergraduate psychology class, you probably have heard about the experiment where monkeys, having previously shown little or no preference between red, blue, and green M&Ms are offered them in pairs. First blue and red is offered, and the one not chosen (say blue) is offered against green. About 2/3 of the monkeys choose green. Psychologists claim this is a sign of cognitive dissonance: information is ignored or used selectively to confirm biases. If blue is not chosen in the first round, it must be “bad”, so it is less likely to be chosen in the second round. Not so fast! If the monkey does have a preference among the colors, then perhaps the monkey is acting consistently. There are six choices for an ordering of the colors:

If you have taken an undergraduate psychology class, you probably have heard about the experiment where monkeys, having previously shown little or no preference between red, blue, and green M&Ms are offered them in pairs. First blue and red is offered, and the one not chosen (say blue) is offered against green. About 2/3 of the monkeys choose green. Psychologists claim this is a sign of cognitive dissonance: information is ignored or used selectively to confirm biases. If blue is not chosen in the first round, it must be “bad”, so it is less likely to be chosen in the second round. Not so fast! If the monkey does have a preference among the colors, then perhaps the monkey is acting consistently. There are six choices for an ordering of the colors: