It is the time of the year for resolutions. Resolutions help define what we would like to be, but are damned hard things to follow through on. As Paul Rubin points out, gyms will be overrun for a few weeks with “resolvers” (or, as my former personal trainer called them “resolutionists”) before the weight room empties again. I’ve been as guilty as any in this regard: it is no coincidence that my gym membership runs January 15-January 15 and that I renew it each year with the best intents, and the worst results. Paul suggests an OR view of resolutions:

…the New Year’s resolution phenomenon offers a metaphor for O. R. practice. The “resolver” diets, exercises, stops smoking or whatever for a while because the “boss” (their conscience) is paying attention. When the “boss” stops watching, the “resolver” makes excuses for why the new regime is too difficult, and reverts to previous behavior. An O. R. solution to a business problem that is implemented top-down, without genuine commitment by the people who actually have to apply the solution (and change behaviors in doing so), is likely to end up a transient response leading to a return to the previous steady state.

So, in keeping with an operations research view of resolutions, I’ve been thinking about my resolutions with a particular focus on variables (what choices can I make), constraints (what are the limits on those choices) and objectives (what I am trying to accomplish). It does no good to define objectives and go willy-nilly off in those directions without also defining the constraints that stop me from doing so. But, of course, a creative re-definition or expansion of variables might let me find better solutions.

I have personal resolutions, and take inspiration from people around me who are able to transform themselves (yes, BB, I am talking about you!). But I also have some professional resolutions. So, here they are, and I hope they have been improved by an operations research view:

- Make time for research. This might seem to be a funny resolution: isn’t that a big part of what professors do? Unfortunately, I have taken an administrative role, and there is a never-ending list of things to do. Short term, it seems if I will be a better Associate Dean if I get on with the business of Associate Deaning, but long-term I know I will be a better Associate Dean if I keep active in research. The decision model on time allocation has to be long term, not short term.

- Do what makes me happiest. But where will the time come from? I need to stop doing some things, and I have an idea of what those are. I have been very fortunate in my career: I’ve been able to take part in the wide varieties of activities of a well-rounded academic career. Not all of this gives me equal pleasure. Some aspects (*cough* journals *cough*) keep me up at night and are not my comparative advantage. So now is the time to stop doing some things so I can concentrate on what I like (and what I am comparatively good at). While many of my decisions in my life can be made independently, time is a major linking constraint.

- Work harder at getting word out about operations research. This has not been a great year for this blog with just 51 posts. I don’t want to post just for the sake of posting, but I had lots of other thoughts that just never made it to typing. Some appeared as tweets, but that is unsatisfying. Tweets are ephemeral while blog entries continue to be useful long after their first appearance. This has been a major part of my objective function, but I have been neglecting it.

- Truly embrace analytics and robustness. While “business analytics” continues to be a hot term, I don’t think we as a field have truly internalized the effect of vast amounts of data in our operations research models. There is still too much a divide between predictive analytics and prescriptive analytics. Data miners don’t really think of how their predictions will be used, while operations researchers still limit themselves to aggregate point estimates of values that are best modeled as distributions over may, predictable single values. Further, operations research models often create fragile solutions. Any deviation from the assumptions of the models can result in terrible situations. A flight-crew schedule is cheap to run until a snowstorm shuts an airport in Chicago and flights are cancelled country-wide due to cascading effects. How can we as a field avoid this “curse of fragility”? And how does this affect my own research? Perhaps this direction will loosen some constraints I have seen as I ponder the limits of my research agenda.

- Learn a new field. While I have worked in a number of areas over the years, most of my recent work has been in sports scheduling. I started in this are in the late 90s, and it seems time to find a new area. New variables for my decision models!

Happy New Year, everyone, and I wish you all an optimal year.

This entry is part of the current INFORMS Blog Challenge.

Don talked about a system they have put in place to handle buses, trollies, and other transportation systems that have multiple vehicles going over the same routes. I am sure we have all had the frustration of waiting a long time for a bus, only to have three buses (all running the same route) appear in quick succession.

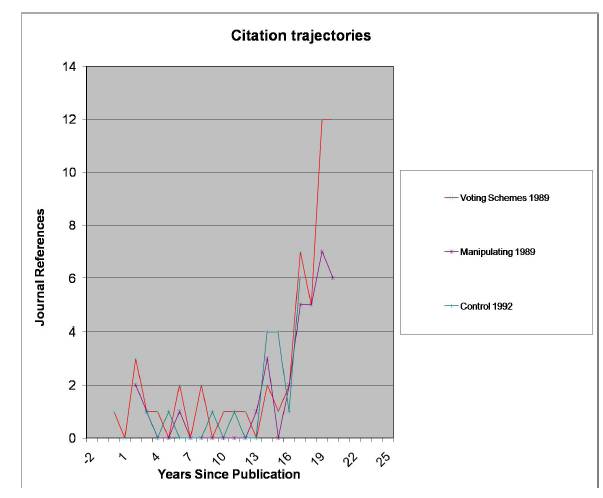

Don talked about a system they have put in place to handle buses, trollies, and other transportation systems that have multiple vehicles going over the same routes. I am sure we have all had the frustration of waiting a long time for a bus, only to have three buses (all running the same route) appear in quick succession.  But then something amazing happened about 5 years ago: people started referring to the papers! The references were mainly in computer science, but at least the papers were being recognized. The counts of these papers in the

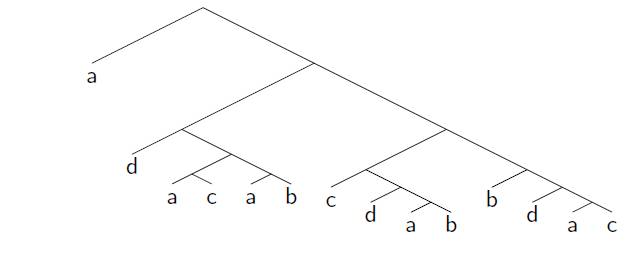

But then something amazing happened about 5 years ago: people started referring to the papers! The references were mainly in computer science, but at least the papers were being recognized. The counts of these papers in the Can you do this for four candidates? If you want “a” to win, “a” must be in the top cycle: the group of candidates (perhaps the entire set of candidates) who all beat all the other candidates. The “Condorcet winner” is the minimal top cycle: if some candidate beats all the other candidates one-on-one, then that candidate must win any voting tree it occurs in. So, assuming “a” is in the top cycle, can you create a voting tree so that “a” wins with four candidates? The answer is yes, but it is a bit complicated: first “a” goes against “c” with the winner against “d” then the winner against “b” who plays the winner of (“a” goes against “b” with the winner against “d” …) …. actually, the minimum tree has 14 leaves! I am biased, but I think the tree is beautiful, but it goes to show how hard it is to manipulate agendas without knowledge of others’ preferences. I am in the process of generating the trees on 4 candidates: there is a very natural rule (“Copeland winner with Copeland loser tie break”: see the presentation for definitions) that requires more than 32 leaves (if an implementation tree for it exists).

Can you do this for four candidates? If you want “a” to win, “a” must be in the top cycle: the group of candidates (perhaps the entire set of candidates) who all beat all the other candidates. The “Condorcet winner” is the minimal top cycle: if some candidate beats all the other candidates one-on-one, then that candidate must win any voting tree it occurs in. So, assuming “a” is in the top cycle, can you create a voting tree so that “a” wins with four candidates? The answer is yes, but it is a bit complicated: first “a” goes against “c” with the winner against “d” then the winner against “b” who plays the winner of (“a” goes against “b” with the winner against “d” …) …. actually, the minimum tree has 14 leaves! I am biased, but I think the tree is beautiful, but it goes to show how hard it is to manipulate agendas without knowledge of others’ preferences. I am in the process of generating the trees on 4 candidates: there is a very natural rule (“Copeland winner with Copeland loser tie break”: see the presentation for definitions) that requires more than 32 leaves (if an implementation tree for it exists).