Noah Snyder, a doctoral student in mathematics at Berkeley, has a wonderful post on how to be a successful doctoral student (I lost track on where I saw this: if it is from an OR blog, please let me know so I can give credit Thanks to Yiorgos Adamopoulos for his tweet on this). While there is an emphasis on the situation in mathematics, I think the advice he gives is great (for the most part). His thoughts revolve around the topics:

- Prioritize reading readable sources

- Build narratives

- Study other mathematician’s taste

- Do one early side project

- Find a clump of other graduate students

- Cast a wide net when looking for an advisor

- Don’t just work on one thing

- Don’t graduate until you have to

I particularly like his “build narratives” advice. Every good piece of research has a story behind it. Why is this research being done? How does it fit? Why should people care about this research (hint: “The literature has a hole which I have now filled” is not a particularly evocative story)? Once that story is found, research directions are clear, and the whole enterprise takes on a new life. Note that the narratives are not the same as a popularization (like, say, a blog posting); the example Noah gives is pretty technical:

In the 80s knot polynomials went through the following transition. First people thought about towers of algebras, then they replaced those with skein theory, then they related those to quantum groups. Attempts at categorification has gone backwards through this progression. First Frankel and Crane wanted to categorify quantum groups, when that proved difficult Khovanov instead categorified the skein theory. Finally, in Khovanov’s HOMFLY homology paper he went all the way back to categorifying towers of algebras and replacing them with towers of categories.

There is a narrative there, and it is one that will resonate with the research audience.

About 22 years ago, when I was a doctoral student trying to finish my dissertation, I had a terrible time putting things together. I had lots of papers (it was a great time to be a doctoral student at Georgia Tech: lots of great young faculty to work with) but I couldn’t put it together into a dissertation. I remember getting snowed in during a rare Atlanta snowstorm and sitting down with a stack of index cards, on which I wrote all that I knew about or wanted to explore further. I spent the next day or two shuffling the cards and putting them in different groupings and orders. Out of that, a story finally appeared. I don’t think it was a great story (the title of my dissertation was “Networks with Specially Structured Side Constraints”), but it was enough of a story to shape the disseration and provide a research agenda for the first years after graduation.

I see a lot of students who present work who don’t go beyond “My advisor told me this was a good problem”. I think thinking about the narrative would do a lot of us good.

The only piece of advice I would disagree with from Noah’s post is the last one, where he suggests delaying graduation. This may be forced by his field, which is extremely competitive, but I strongly disagree with that advice in operations research. In general, I think students should get what they can out of a doctoral program, and push themselves to move on. Our doctoral students make perhaps $20,000 a year or a bit more: a comfortable graduate student living, of course. But faculty salaries will be many times that amount, and even postdocs will pay better. Don’t stay in school hoping for that one more paper that will put you over the top. If you have only one more paper in you, you won’t last in this field anyway. If you have more than that, do them at the next phase of your career.

I am not suggesting rushing through your doctoral program, but once you finish your fifth year here at CMU (we admit students from the bachelors degree, and give a masters degree along the way), we’d really like for you to think about moving on, and I think that is a pretty good general outline.

If you are a doctoral student, or a researcher of any age for that matter, I highly recommend reading Noah’s comments.

Laura McLay, author of

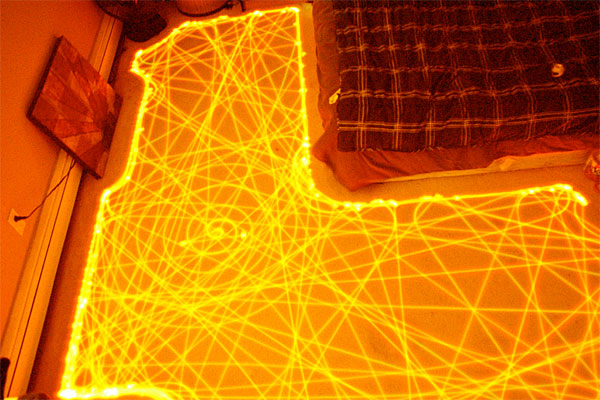

Laura McLay, author of  Today, I came across a picture of a

Today, I came across a picture of a