After a few years hiatus, I finally got back to seeing a doctor for an annual physical last week. For a 51-year-old male with a fondness for beer, I am in pretty good shape. Overweight (but weighing a bit less than six months ago), pretty good blood pressure (123/83), no cholesterol issues, all without the need for an drug regime.

Once you hit your mid-to-late 40s (and if you are a male), doctors begin to obsess about your prostate. There is a good reason for this: prostate cancer is the second most common reason for cancer death among males (next to lung cancer). So doctors try to figure out whether you have prostate cancer.

However, there is a downside to worrying about the prostate. It turns out that lots of men have prostate cancer, and most men will die of something else. The cancer is often slow growing and localized, making it less of a worry. Cancer treatment, on the other hand, is invasive and risky, causing not only death through the treatment (rare but not negligible) but various annoying issues such as impotence, incontinence, and other nasty “in—“s. But if the cancer is fast growing, then it is necessary to find it as early as possible and aggressively treat it.

So doctors want to check for prostate cancer. Since the prostate is near the surface, the doctor can feel the prostate, and my doctor did so (under the watchful gaze of a medical student following her and, as far as I know, a YouTube channel someplace). When I say “near the surface”, I did not mention which surface: if you are a man of a certain age, you know the surface involved. The rest of you can google “prostate exam” and spend the rest of the day trying to get those images out of your mind.

Before she did the exam, we did have a conversation about another test: PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen) testing. This is a blood test that can determine the amount of a particular antigen in the blood. High levels are associated with prostate cancer. My doctor wanted to know if I desired the PSA test.

Well, as I was recovering from the traditional test (she declared that my prostate felt wonderful: if it were a work of art, I own the Mona Lisa of prostates, at least by feel), I decided to focus on the decision tree for PSA testing. And here I was let down by a lack of data. For instance, if I have a positive PSA test, what is the probability of my having prostate cancer? More importantly, what is the probability that I have the sort of fast growing cancer for which aggressive, timely treatment is needed? That turns out to be quite a complicated question. As the National Cancer Institutes of the NIH report, there is not any clear cutoff for this test:

PSA test results show the level of PSA detected in the blood. These results are usually reported as nanograms of PSA per milliliter (ng/mL) of blood. In the past, most doctors considered a PSA level below 4.0 ng/mL as normal. In one large study, however, prostate cancer was diagnosed in 15.2 percent of men with a PSA level at or below 4.0 ng/mL (2). Fifteen percent of these men, or approximately 2.3 percent overall, had high-grade cancers (2). In another study, 25 to 35 percent of men who had a PSA level between 4.1 and 9.9 ng/mL and who underwent a prostate biopsywere found to have prostate cancer, meaning that 65 to 75 percent of the remaining men did not have prostate cancer (3).

In short, even those with low PSA values have a pretty good chance of having cancer. There is the rub between having a test “associated with” a cancer, and having a test to determine a cancer. Statistical association is easy: the correlation might be very weak, but as long as it is provably above zero, the test is correlated with the disease. Is the correlation high enough? That depends on a host of things, including an individual’s view of the relative risks involved. But this test is clearly not a “bright line” sort of test neatly dividing the (male) population into those with cancers that will kill them and those without such cancers.

In the days since my doctor’s appointment, there have been a slew of articles on PSA testing, due to the US Preventative Services Task Force moving towards declaring that PSA testing has no net benefit. The Sunday New York Times Magazine has an article on prostate screening. The article includes a wonderfully evocative illustration of the decision to be made:

David Newman, a director of clinical research at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in Manhattan, looks at it differently and offers a metaphor to illustrate the conundrum posed by P.S.A. screening.

“Imagine you are one of 100 men in a room,” he says. “Seventeen of you will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, and three are destined to die from it. But nobody knows which ones.” Now imagine there is a man wearing a white coat on the other side of the door. In his hand are 17 pills, one of which will save the life of one of the men with prostate cancer. “You’d probably want to invite him into the room to deliver the pill, wouldn’t you?” Newman says.

Statistics for the effects of P.S.A. testing are often represented this way — only in terms of possible benefit. But Newman says that to completely convey the P.S.A. screening story, you have to extend the metaphor. After handing out the pills, the man in the white coat randomly shoots one of the 17 men dead. Then he shoots 10 more in the groin, leaving them impotent or incontinent.

Newman pauses. “Now would you open that door?”

Is more information better? To me, information matters only if it changes my actions. Would a “positive” PSA test (whatever that means) lead me to different health-care decisions? And is it really true that more information is always better? Would my knowing that I, like many others, had cancerous prostate cells (without knowing if they will kill me at 54 or 104) really improve my life?

Perhaps in a few years, we’ll have a some advances. Ideal, of course, would be a test that unmistakably can determine if a man has a prostate cancer that, untreated, will kill him. Next best would be better, more individual models that would say, perhaps “A 53 year old male, with normal blood pressure and a fondness for beer, with a prostate shape that causes angels to sing, and a PSA value of 4.1 has an x% chance of having a prostate cancer that, untreated, will kill him with five years.” Then I would have the data to make a truly informed decision.

This year, I opted against the PSA test, and everything I have read so far has made me more confident in my decision. Of course, I did not necessarily opt out of PSA testing forever and ever: I get to make the same decision next year, and the one after that, and the one after that…. But I will spend the time I save in not worrying about PSA testing by working out more at the gym (and maybe adding a bit of yoga to the regime). That will, I think, do me much more good.

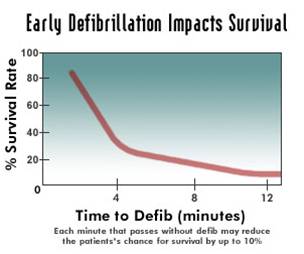

The graph attached (not from Laura, available in lots of places on the internet) shows a sharp dropoff as the minutes tick away.

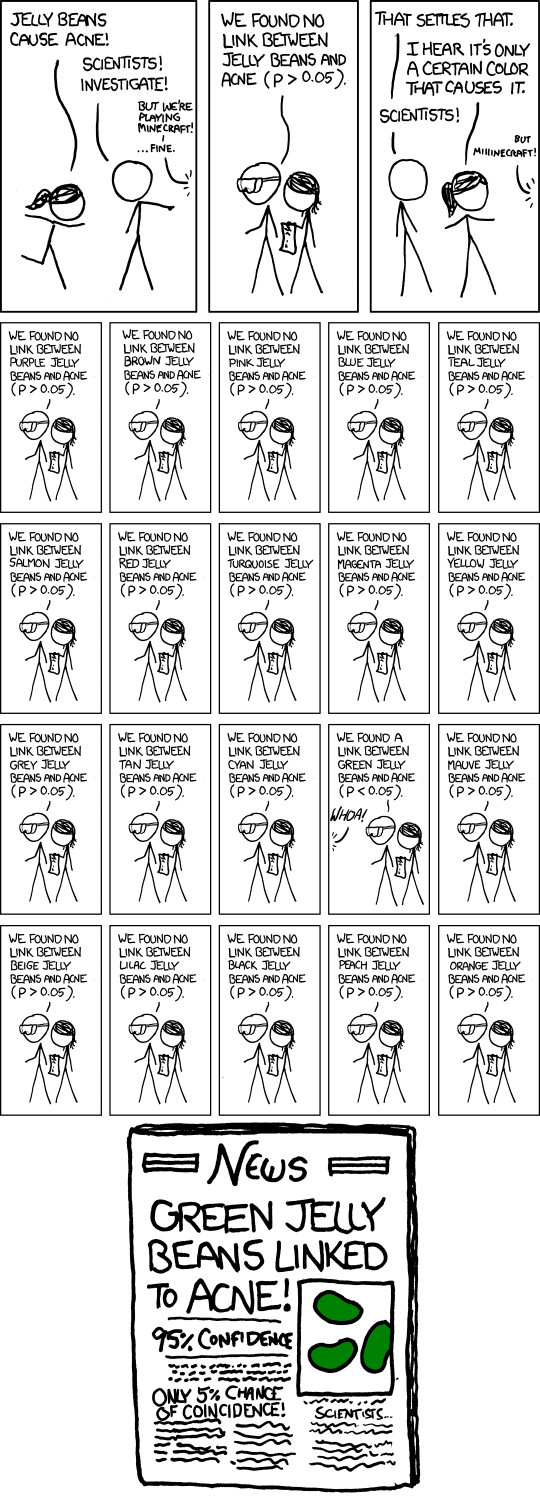

The graph attached (not from Laura, available in lots of places on the internet) shows a sharp dropoff as the minutes tick away. If you test lots of things, you will come up with “significant” results.

If you test lots of things, you will come up with “significant” results.