Last year, a group of students in one of my classes did a project on designing a grizzly bear habitat, inspired by the work at Cornell’s wonderful Institute for Computational Sustainability. In that project, the goal was to pick out a collection of geographic areas that formed a contiguous zone that the grizzly’s could move freely through. As the ICS description says:

Land development often results in a reduction and fragmentation of natural habitat, which makes wildlife populations more vulnerable to local extinction. One method for alleviating the negative impact of land fragmentation is the creation of conservation corridors, which are continuous areas of protected land that link zones of biological significance.

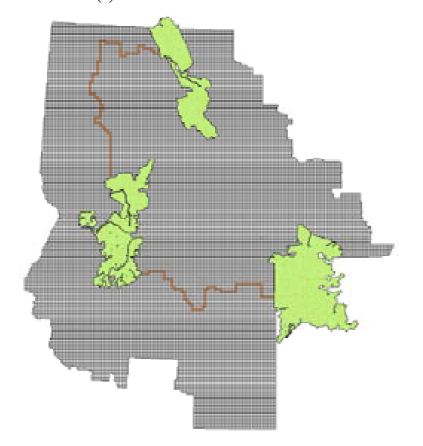

My colleague, Willem van Hoeve, had worked on variants of this problem and had some nice data for the students to work with. The models were interesting in their own right, with the “contiguity” constraints causing the most challenge to the students. The results of the project were corridors that were much cheaper (by a factor of 10) than the estimates of the cost necessary to support the wildlife. The students did a great job (as Tepper MBA students generally do!) using AIMMS to model and find solutions (are there other MBA students who come out knowing AIMMS? Not many I would bet!). But I was left with a big worry. The goal here was to find corridors linking “safe” regions for the grizzlies. But what keeps the grizzlies in the corridors? If you check out the diagram (not from the student project but from a research paper by van Hoeve and his coauthors), you will see the safe areas in green, connected by thin brown lines representing the corridors. It does seem that any self-respecting grizzly would say: “Hmmm…. I could walk 300 miles along this trail they have made for me, or go cross country and save a few miles.” The fact that the cross country trip goes straight through, say, Bozeman Montana, would be unfortunate for the grizzly (and perhaps the Bozemanians). But perhaps the corridors could be made appealing enough for the grizzlies to keep them off the interstates.

My colleague, Willem van Hoeve, had worked on variants of this problem and had some nice data for the students to work with. The models were interesting in their own right, with the “contiguity” constraints causing the most challenge to the students. The results of the project were corridors that were much cheaper (by a factor of 10) than the estimates of the cost necessary to support the wildlife. The students did a great job (as Tepper MBA students generally do!) using AIMMS to model and find solutions (are there other MBA students who come out knowing AIMMS? Not many I would bet!). But I was left with a big worry. The goal here was to find corridors linking “safe” regions for the grizzlies. But what keeps the grizzlies in the corridors? If you check out the diagram (not from the student project but from a research paper by van Hoeve and his coauthors), you will see the safe areas in green, connected by thin brown lines representing the corridors. It does seem that any self-respecting grizzly would say: “Hmmm…. I could walk 300 miles along this trail they have made for me, or go cross country and save a few miles.” The fact that the cross country trip goes straight through, say, Bozeman Montana, would be unfortunate for the grizzly (and perhaps the Bozemanians). But perhaps the corridors could be made appealing enough for the grizzlies to keep them off the interstates.

I thought of this problem as I was planning a trip to China (which I am taking at the end of November). After seeing a picture of a ridiculously cute panda cub (not this one, but similarly cute), my seven-year-old declared that we had to see the pandas. And, while there are pandas in the Beijing zoo, it was necessary to see the pandas in the picture, who turned out to be from Chengdu. So my son was set on going to Chengdu. OK, fine with me: Shanghai is pretty expensive so taking a few days elsewhere works for me.

As I explored the panda site, I found some of the research projects they are exploring. And one was perfect for me!

Construction and Optimization of the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding Ecological System

I was made for this project! First, I have the experience of watching my students work on grizzly ecosystems (hey, I am a professor: seeing a student do something is practically as good as doing it myself). Second, and more importantly, I have extensive experience in bamboo, which is, of course, the main food of the panda. My wife and I planted a “non-creeping” bamboo plant three years ago, and I have spent two years trying to exterminate it from our backyard without resorting to napalm. I was deep into negotiations to import a panda into Pittsburgh to eat the cursed plant before I finally seemed to gain the upper hand on the bamboo. But I fully expect the plant to reappear every time we go away for a weekend.

I was made for this project! First, I have the experience of watching my students work on grizzly ecosystems (hey, I am a professor: seeing a student do something is practically as good as doing it myself). Second, and more importantly, I have extensive experience in bamboo, which is, of course, the main food of the panda. My wife and I planted a “non-creeping” bamboo plant three years ago, and I have spent two years trying to exterminate it from our backyard without resorting to napalm. I was deep into negotiations to import a panda into Pittsburgh to eat the cursed plant before I finally seemed to gain the upper hand on the bamboo. But I fully expect the plant to reappear every time we go away for a weekend.

Between my operations research knowledge and my battle-scars in the Great Bamboo Battle, I can’t think of anyone better to design Panda Ecological Systems. So, watch out “Chengdu Research Base on Giant Panda Breeding”: I am headed your way and I am ready to optimize your environment. And if I sneak away with a panda, rest assured that I can feed it well in Pittsburgh.

This is part of the INFORMS September Blog Challenge on operations research and the environment.

There is a

There is a